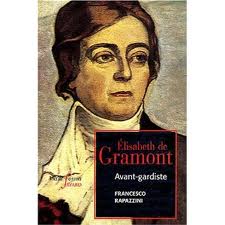

I’ve begun a new literary adventure, and I look forward to sharing it with you in the year to come. I’ll be translating the raucous biography of an incredible woman, Élisabeth de Gramont, from French into English. If you read French, you can buy the book here.

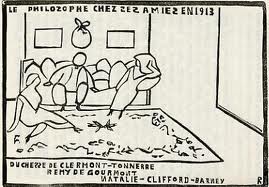

2018 will mark the 100th anniversary of the first modern marriage contract between two women, made by Élisabeth, Duchess of Clermont-Tonnèrre, a central figure in the artistic and political history of modern France, and her “eternal mate,” Natalie Barney, that consummate American in Paris.

The amazing untold story of a secret lesbian marriage

Their beautiful, radical, non-monogamous and staunchly faithful union lasted a lifetime until Élisabeth’s death in 1954, which shattered Natalie to the core. Astonishingly, all this was kept secret until Francesco Rapazzini published his biography in 2004, with the full support and generous cooperation of Élisabeth’s very private family.

Wild Blue

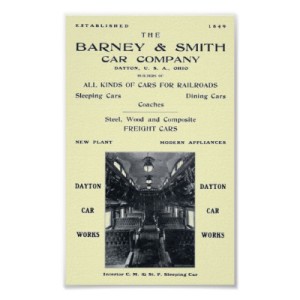

As a daughter of Michigan and a lesbian with a family business background of my own, I knew all about the railway carriage heiress of the Belle Époque when I was growing up. It may have been the heyday of NCR, but my father still taught me to pinpoint Dayton, Ohio on the map as the home producer of Barney cars. Barney was a great family business that he rued the end of. For as Walter Matthau’s butler quips famously in A New Leaf, my father (like Natalie herself, whose beautiful French was more 1793 than 1923) was a modern man who liked to keep alive traditions that were dead before he was born.

As I grew older and understood the gayness that he had taken for granted all my life, Dad made it quietly known that the wild child from Cincinnati was no role model. She was a model for bad behavior on par with the wayward Peggy Guggenheim. Certainly not a fit spiritual great-granny for a girl like me. Wild Blue, I always thought of Natalie with her untamed blonde mane and her steel-blue gaze. I’d find myself shaking my head in grudging admiration of her outrageous exploits in Bar Harbor and Washington, not to mention her audacious seduction of Liane de Pougy, the world’s most desirable woman, as a nineteen year-old American in Paris.

It goes without saying that my dance card was never as full, nor were my date nights. In fact we couldn’t have been more different.

Natalie was a much better rider, for one thing. She fenced and spoke French bilingually. My eyes and hair were dark, like Élisabeth’s, and like Lily de Gramont, I had a commanding voice that drew attention, a quick long laugh and a love of the countryside, the water and the wild places. And if my gaze was sometimes just as imposing, it was never predatory. Natalie’s was.

Like every other girl of my ilk, though, I found it hard to ignore Natalie Barney, even though she, too, was dead before my gay history was born. We were worlds apart in many of our tastes if not in our drives. She never set foot in a café, for instance, whereas I could live in them. I prized domestic anchorage; I valued love and loves placed in a lifelong context, while Natalie appeared to have no use for such things as marriage or children or even for making her life with animals. But my God, what a lover….

They got it wrong–for 40 years!

Natalie died in Paris in 1972 when I was seven. I watched and read, during my lifetime, as an entire cottage industry was built up around Barney as a legendary (some would say fatal) seducer, largely for her leading role as a patron of the arts to the Lost Generation. And now I realize that, in key respects, all the scholars and memoirists got it wrong. Like majorly wrong. It’s like that great Cary Brothers song…

Blue eyes, you’re the secret I keep

Cary Brothers, “Blue Eyes” from “Who You Are”

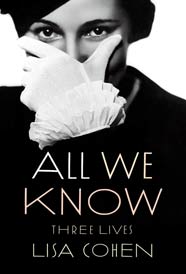

By translating EDG, I’ll start putting it right by getting to know the wonderful secret Natalie kept so close to her heart, hiding her in plain sight. You will not believe the passion, the fireworks, the honesty and the agony in their love letters.

“Je vous présente Élisabeth, la duchesse rouge”

More importantly, I’ll introduce English readers for the first time to the incredibly full and rich (and, yes, complex) life of an extraordinary character in 20th century history. Élisabeth was a Marxist descended from Henri IV who shrugged off the slur “red duchess.” She was a popular author and sculptor and librettist, a music patron and the major clef to Proust’s great roman. Lily was another wild child who would never be tamed. She was the only woman Natalie Barney could never control. Élisabeth was also the clef to Natalie’s own living work of art, the one she dedicated her life to and hoped and dreamed it would become. Above all, Lily loved to laugh.

More importantly, I’ll introduce English readers for the first time to the incredibly full and rich (and, yes, complex) life of an extraordinary character in 20th century history. Élisabeth was a Marxist descended from Henri IV who shrugged off the slur “red duchess.” She was a popular author and sculptor and librettist, a music patron and the major clef to Proust’s great roman. Lily was another wild child who would never be tamed. She was the only woman Natalie Barney could never control. Élisabeth was also the clef to Natalie’s own living work of art, the one she dedicated her life to and hoped and dreamed it would become. Above all, Lily loved to laugh.

So if you are a reader of belles-lettres, a student of French cultural history from the Belle Époque through World War II, or a reader of the biographies and scholarly studies of the great lesbians of the 20th century, I hope you will enjoy my field reports in 2013.

If I complete four pages a day, I should have a draft ready by next Christmas. For now, glad to have you on my rope. We’re off into the wild blue yonder.

In Good Company

By the way, my first impression of this job is that literary translation hasn’t changed much since antiquity. It’s laborious, and taxing, and when you admire the author and have great affection for the subject, like I do, it’s incredibly satisfying. The loneliness sometimes brought about by the solitary nature of the work is more than compensated by the excellent company I keep at the end of my shift. My veteran editor, Jean-Loup Combemale, grew up in Paris on the rue Jacob and visited his grandparents a few doors down from Élisabeth on the rue de la Faisanderie. My able researcher, Vanessa Coulomb, brings an M.B.A.’s focus to the job of helping today’s English readers relate to la vieille France, along with a storied Norman childhood of her own. Thanks in advance to you both.

Acts of love and literature

Given today’s economy—less than 5% of all books sold annually in the US are translations of works published in a foreign language, according to The Nation—a major literary translation is usually an act of love, an undertaking in the great amateur tradition, which Élisabeth herself joined the ranks of when she translated the poems of John Keats as a young woman.

There are those who play for money, babe

There are those who play for fame

There are still those who only play

For the love of the game

T Bone Burnett, “Kill Switch”

from “The Criminal Under My Own Hat”

It’s a band of brothers and sisters I’m proud to be a part of. As I learn more about them and their august tradition dating from the advent of written language, I’ll pass it on. And if you have any questions or interests or stories of your own to tell, please share.